A Missionary Account

“Nearly all homes in coastal farming and fishing villages had an outside toilet, a simple construction rather like a sentry box on a plinth, inside a hole over a chute, with somewhere to place your feet. The chute led directly outside. There was always a bucket of water and a jug for washing your bum after the business was done. From the time piglets were weaned, they were raised to eat human waste. To encourage (compel) them to do that, they were secured by a rope close to the toilet outlet and fed with nothing else except what came down the chute. Once the habit was acquired, the pigs gobbled it up with gusto.”

Despite King David’s moral failings, he is identified as a man after God’s own heart. He was a valiant warrior, a powerful leader, and an elegant composer. His psalms reveal an acquaintance with the divine majesty and a knowledge of the great human predicament. If there is a dominant theme throughout his works, it is the theme of longing. And if there is one lyric that best embodies this longing, it is this one:

One thing I ask from the Lord

this only do I seek:

that I may dwell in the house of the Lord

all the days of my life

to gaze on the beauty of the Lord

and to seek him in his temple.

What draws David is not the Lord’s power or beneficence. Yes, David is fully aware of God’s mercy and kindness. He knows that God is the strength behind his throne and his shield in times of trouble. But these things are peripheral to David’s deepest desire. What David longs for above all is to behold the beauty of the Lord.

The word that David uses for beauty refers to that which is delightful. David is not speaking of his response to some vision as though delight originates in human experience. He is not seeking to be delighted. For David, beauty is not in the eyes of the beholder. God is beautiful whether David sees it or not. God’s nature and character are delight itself; they do not require affirmation from angel or human to be beautiful. The substance of the Lord’s beauty is his own goodness, not a creature’s response. In the words of the old hymn, God is beautiful even though the eyes of sinful man his glory may not see. The Lord is beautiful because he is beauty itself.

The poem Ode on a Grecian Urn, by John Keats, includes this well-known line: “Beauty is truth, truth beauty.” Some are wary of this pronouncement, warning that beauty can be misleading. After all, does not the scripture say that charm is deceitful, and beauty is vain? Peter tells us that worldly beauty is only outward adornment and not an image of the inner self. But God’s beauty is not worldly; it is the outshining of his being. Paul says that this divine beauty can be seen in what God has made. And if, as Isaiah declares, he is the God of truth, then Keats is absolutely right, even if he didn’t realize why. David would wholeheartedly agree. Beauty is the revelation of truth, and truth is the substance of beauty.

Because there is no truth in Satan, beauty is inaccessible and incomprehensible to him—and he reviles what he does not understand. All he knows is the desire for domination and the compulsion to destroy what he cannot control. Paul’s description of humanity’s fall aptly summarizes the devil’s as well:

Although they knew God, they neither glorified him as God nor gave thanks to him, but their thinking became futile and their foolish hearts were darkened . . . they exchanged the truth about God for a lie, and worshiped and served created things rather than the Creator.

Here is the radical shift common to humans and angels. Transcendent knowledge is replaced by material ignorance; truth and beauty, by deceit and ugliness. This is no mean deterioration; it is a fundamental change of reality. Like Fitzgerald’s Gatsby, our minds once romped like the mind of God, but we are now locked in a spiritless finitude, lost in a mechanical, disenchanted world devoid of beauty.

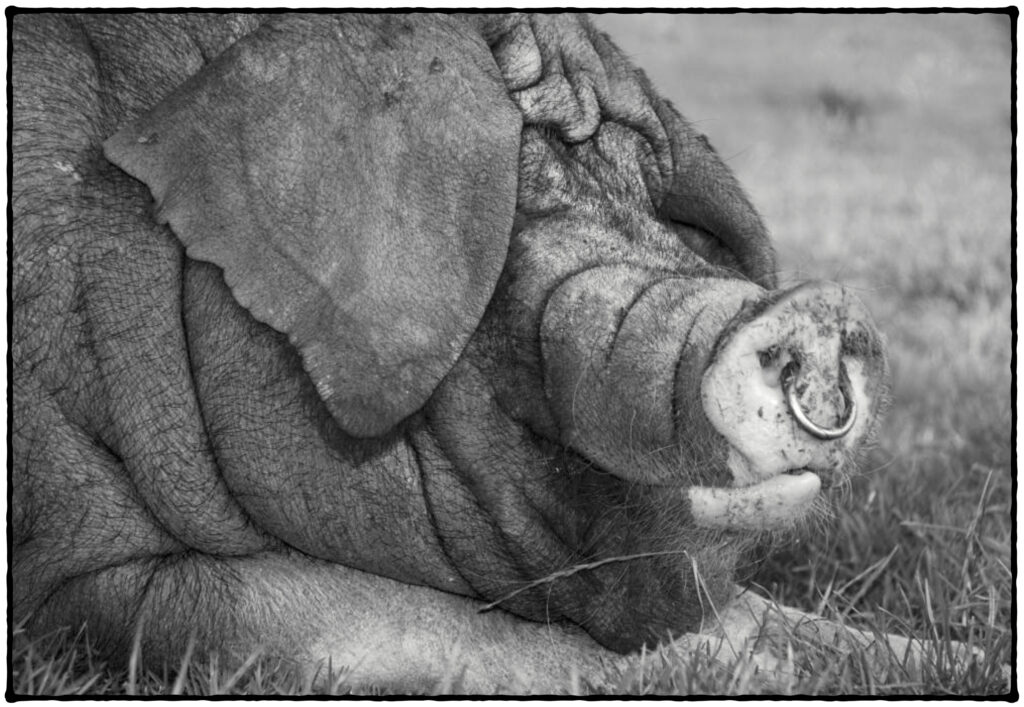

But ugliness is Satan’s aesthetic, and through pervasive sensory arguments and relentless cultural pressures he is teaching humans to love the ugly and reject the beautiful. His curriculum has been implemented across the cultural landscape, from the arts to fashion to the media. A couple of cases might illustrate his multifaceted strategy.

One prominent example is the systematic distortion of body image. Satan is perverting the ideal of human physical beauty by advocating images of the abnormal and grotesque. Plastic surgery, extreme body modification, obesity, and the like, which have long been considered strange and repulsive, are now forcefully championed as beautiful. To be clear, Satan is not advocating a gracious acceptance of those who look different, nor is he prioritizing the inner beauty of which Peter speaks. The devil is insisting that we embrace physical defect, deformity, and deviance as beautiful; and when the ugly becomes the beautiful, the concept of beauty no longer references truth. Self-admiration and rebellion become the standards of judgment, and the connection between truth and beauty is severed. Wickedness judges itself beautiful.

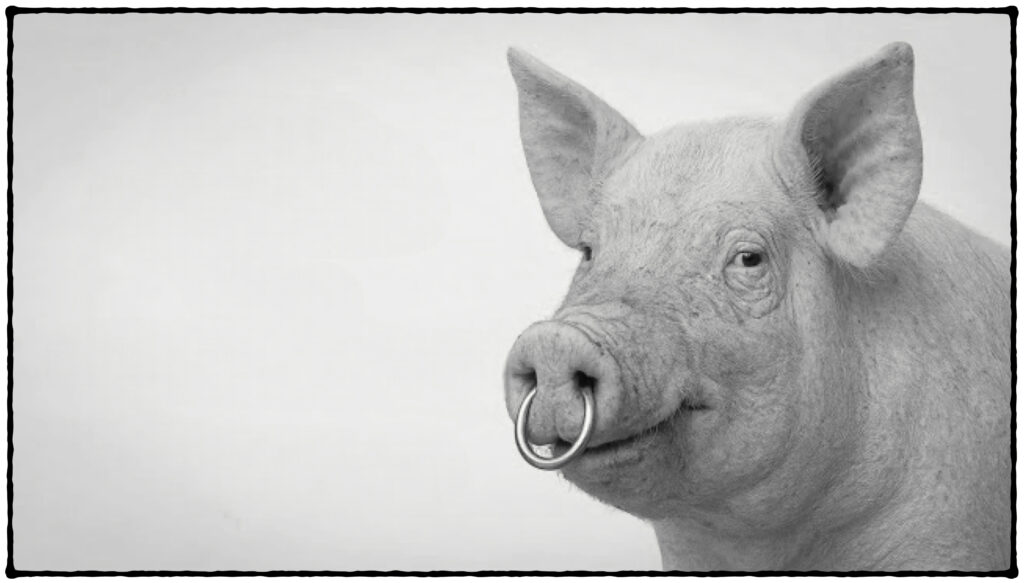

Closely related to this—perhaps the opposite pole—is the hyper-sexualization of the human body. Although the male body is becoming a target too, this sexualization is overwhelmingly centered on the female form. (It seems that the devil cannot fully counter this elemental human bias.) Even those women who loudly protest being objectified still seek to be objects of desire, presenting themselves as robustly sexual creatures. The crassest example, of course, is pornography, which has risen from the societal dung heap to a place of transgressive status. This sexualization of the female body is one of the effects of the fall. (The biblical record reveals that Satan and his ousted angels were not exempt from the lust for female flesh either.) The devil’s success has been to fetishize the female form— and he’s currently working hard to do the same with the male body. Sexualization of the human body transforms God’s beautiful work into an a garish idol of human sensuality, like a gold ring in a pig’s snout.

These are but two examples of the battle to define beauty which rages across the social and creative spectrums. The devil has relentlessly thrust his warped aesthetic into the fashion industry, the fine arts, literature, music, theater, film, and architecture; and his human allies loudly condemn those who question or refute it. Underlying everything is Satan’s three-fold agenda: to repudiate the work of the creator, to refashion the world in his own image, and to enslave a sinful humanity whose destiny is destruction, whose god is their stomach, and whose glory is their shame.

All that stands between Satan’s uncontested domination is the church’s faithful and courageous witness to the truth and true beauty of the Lord.