“Get yourself ready! Stand up and say to them whatever I command you. Do not be terrified by them, or I will terrify you before them.”

Jeremiah 1:17

God is not above employing coercion to get what he wants. When he told Isaiah, “My purpose will stand, and I will do all that I please,” he meant it. I pity the fool who thinks otherwise. And that goes for friend and foe alike.

The road to the Promised Land is littered with the carcasses of those who thought they had a better idea. If the Exodus teaches us anything, it’s that you don’t ever just say “no” to the Almighty. Even Job, one of God’s special favorites, learns this the hard way. “No purpose of yours can be thwarted,” Job stammers, the last of his self-righteousness dribbling from him like a guy with a swollen prostate.

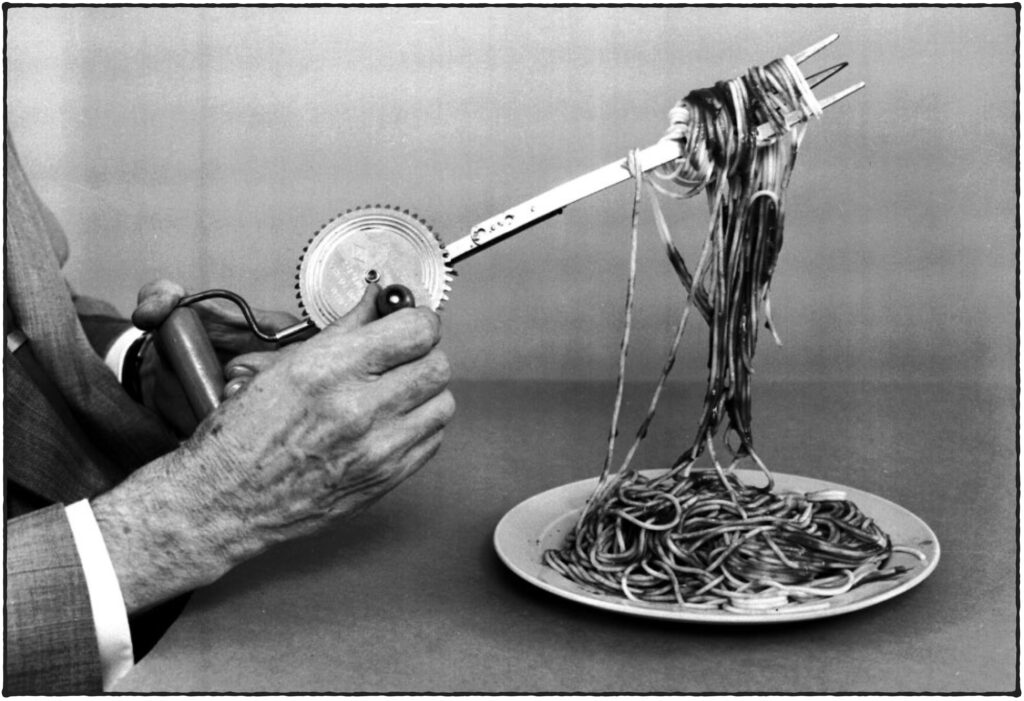

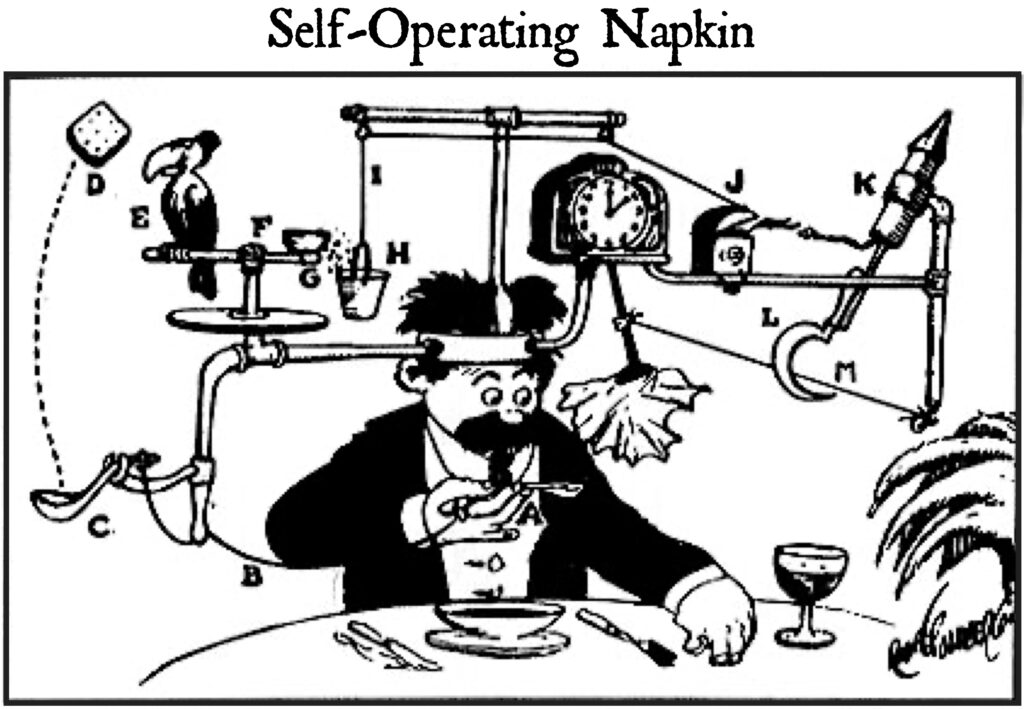

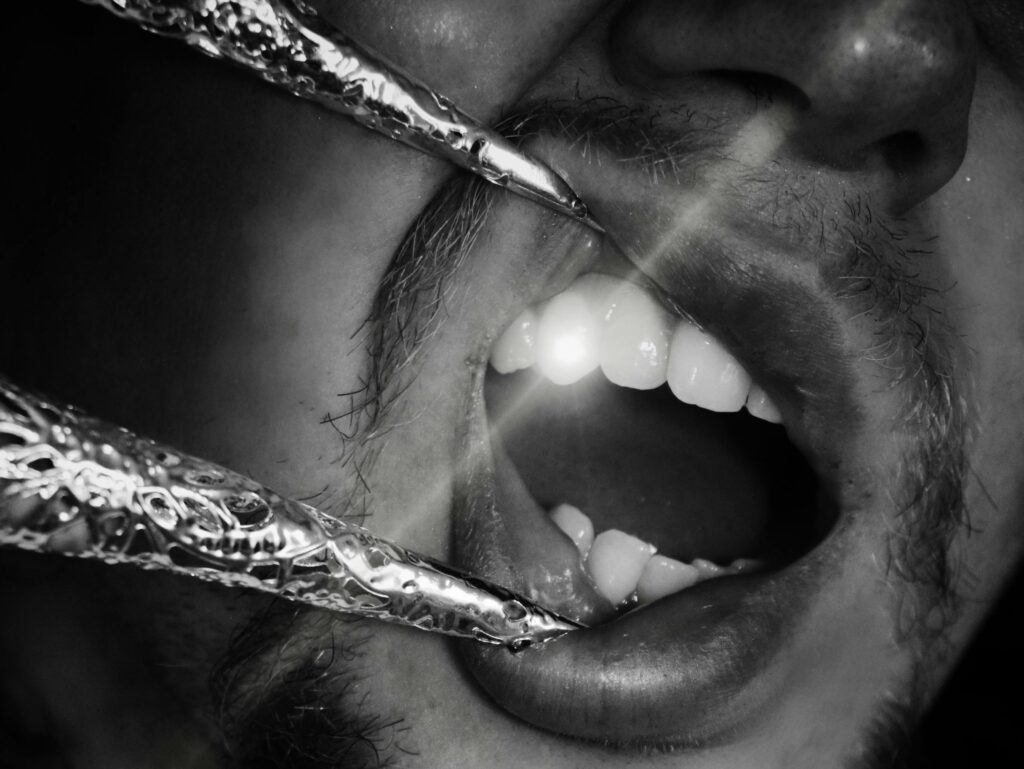

Things get especially interesting, however, when the squeeze to comply comes from within. When God annexes you, he downloads a third-party program that infects your soul and overrides all your previous command authorizations. Jeremiah recounts it this way: The Lord reached out his hand and touched my mouth and said to me, “I have put my words in your mouth.” Ezekiel has a strikingly similar experience: He said to me, “Son of man, eat what is before you, eat this scroll; then go and speak to the people of Israel.” So I opened my mouth, and he gave me the scroll to eat. Then he said to me, “Son of man, eat this scroll I am giving you and fill your stomach with it.” You may like the menu options or you may not, but you’re going to eat what you’re served.

And that’s when the real trouble begins. Once the download is complete, once the Word and Spirit are embedded in your soul, you are not your own. You are God’s property and an instrument for his purposes. In Ezekiel’s case, the mandate came immediately after the scroll entrée. So I ate it, he recounts. He then said to me: “Son of man, go now to the people of Israel and speak my words to them.” As if this command wasn’t forceful enough, God adds, “You must speak my words to them, whether they listen or fail to listen.” Ezekiel has been called, culled, consecrated, and commanded. And when God plucks and programs you for his purposes, resistance is futile.

Although many have tried. King David gave it a shot: I will put a muzzle on my mouth while in the presence of the wicked, he vows. So I remained utterly silent, not even saying anything good. Apparently this doesn’t go so well. He quickly adds, But my anguish increased; my heart grew hot within me. While I meditated, the fire burned. Then I spoke with my tongue. Jeremiah reports a virtually identical experience: But if I say, “I will not mention his word or speak anymore in his name,” his word is in my heart like a fire, a fire shut up in my bones. The inner pressure becomes intolerable. I am weary of holding it in, confesses the prophet. Indeed, I cannot. When you gotta go, you gotta go.

This experience isn’t limited to the Old Testament boys. The death and resurrection of Jesus made Mount Sinai look like a backyard barbecue. The apostles are literally beside themselves as the newly unleashed Holy Ghost transforms them from uneducated oafs and pietistic prunes into God-smacked, radioactive oracles. When Peter and John are ordered to stop speaking of the risen Jesus, they reply, “Which is right in God’s eyes: to listen to you, or to him? You be the judges! As for us, we cannot help speaking about what we have seen and heard.” Paul confesses the same thing. I am compelled to preach, he declares. Woe to me if I do not preach the gospel. Let it flow or you’re gonna blow.

None of this makes much sense to those for whom God is a vague notion or faith is an add-on. How can you explain spiritual compulsion to the religiously content? Many years ago, I was a part of a small prayer meeting. After a series of tame, sapless prayers, I earnestly expressed to the group a dissatisfaction with our spiritual sleepiness and my desire for a consuming visitation. One of the participants, a visiting pastor, looked at me, incredulous, and exclaimed, “What do you want, to glow in the dark?” Most Christians wouldn’t be as blunt, but sometimes I wonder if they have ever experienced—or would even want to experience—hardcore spiritual annexation.

I myself am not sure what to make of all this. My default setting seems to be discontent, not in the sense that I’m dissatisfied with what I have so freely been given, but rather that I feel distressingly underutilized. God has poured more into me than I am pouring out, and the pressure behind the dam—whether it be impatience, ignorance, or disobedience—is at critical levels. I know that there are winters of discontent as we wait for God’s timing, but I’m getting tired of treading the pilgrim way in snowshoes.

What brings me a modicum of comfort is knowing that mine is not a singular malady. For 2000 years Christians have grappled with a God who chooses men and women to display his glory. And who is equal to such a task? asks Paul. To this end, he writes, I strenuously contend with all the energy Christ so powerfully works in me. And this is also my comfort—though a scant one. This inward pressure that is consuming me is a good thing. As Paul reassures us, it is God who works in you to will and to act in order to fulfill his good purpose. God is my problem.

Take heart, O agitated soul. The one who calls you is faithful, and he will do it. Just don’t get in his way.