“Repent therefore, and turn back, that your sins may be blotted out.”

Acts 3:19

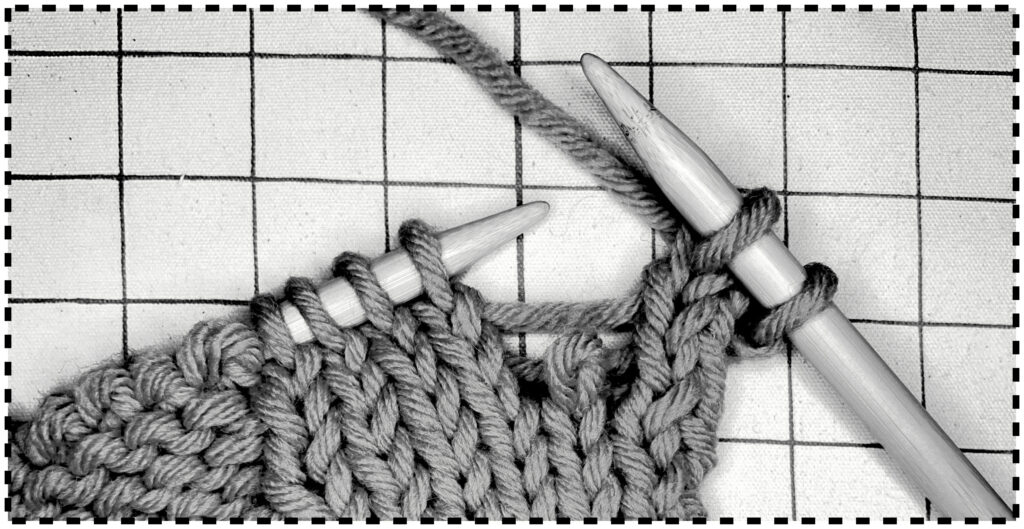

My wife is an avid and skilled knitter. She regularly masters complex patterns demanding multiple yarn colors, and she often employs up to five needles at the same time. Many times she has discovered errors in published pattern charts or has modified rows and stitches to customize her project. Her closet is a trophy case of beautiful scarves, cardigans, sweaters, leggings, and seasonal decor. Her socks are favorite gifts for family and friend alike. Every Wednesday evening she hosts “Knit Night” for a group of women who spend a couple of hours each week chatting and working on their own projects. She’s a yarn Yoda.

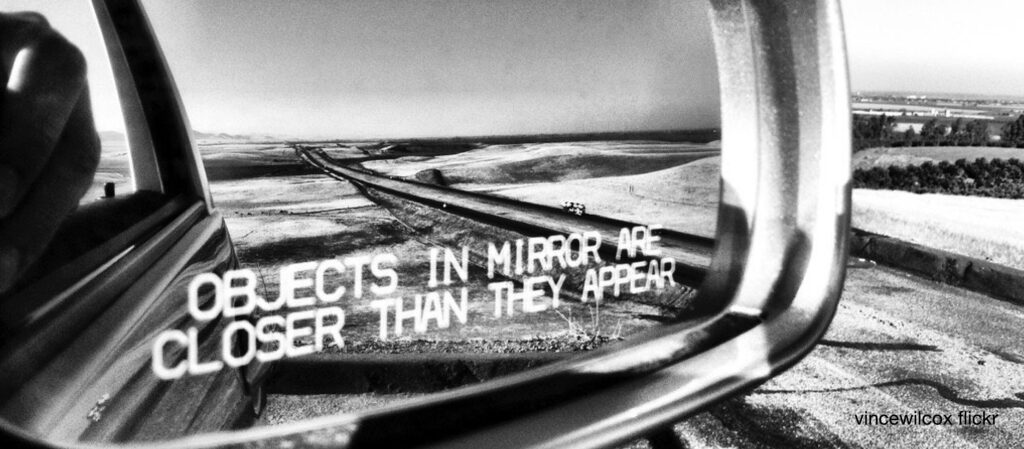

Every so often, however, she will discover that her row or stitch count is off. When that happens, she pauses with a frown, checks the pattern, and tabs with her finger backwards through the stitches until she locates the problem. Sometimes her friends will bring to her projects gone hopelessly awry and beseech her to search out where they went wrong. My wife will study the problem, then carefully backtrack through the knits and purls until she discovers where her friends got off track. Once she has found the starting point of the problem, she will determine if all it needs is a quick surgical fix or—the knitter’s great dread—if the project will have to be unraveled back to the mistake and begun again correctly from there. More than once my wife has had to unravel one of her own nearly completed projects and to start over from the very beginning. Sometimes you have to go backward to go forward.

This is the whole idea of repentance. To believe in the good news means not only to turn away from unbelief itself but away from all the acts that come from it. When the crowds came to John the Baptist, he insisted that they “bear fruit in keeping with repentance.” This fruit is the reckoning and righting of sinful acts as the evidence of a new life in Christ. The first act of saving faith is repentance.

Not all repentance is created equal, however. It is true that whatever is not of faith is sin. Unbelief is unbelief no matter what it looks like. Even so, salvation does not always demand that we revisit the past. There is the famous (added) account in the gospel of John of the woman caught in adultery. After her accusers leave, Jesus asks her, “Has no one condemned you?” She replies, “No one, Lord.” Jesus then tells her, “Neither do I condemn you; go and sin no more.” The woman’s past is now irrelevant; she need not go back to make things right. The Lord has mended her soul and restored the pattern of the woman’s life.

But some repentance does demand that we revisit the past. Zacchaeus, the diminutive chief tax collector who climbs a tree to see Jesus, is a delightful example. Overjoyed that the Lord should visit his house, Zacchaeus exclaims to Jesus, “Look, Lord! Here and now I give half of my possessions to the poor, and if I have cheated anybody out of anything, I will pay back four times the amount.” Jesus announces, “Today salvation has come to this house!” Unlike the woman caught in adultery, Zacchaeus is able to rectify his notorious history. He does not consider Christ’s grace leave to simply walk away from his past actions but as the motivation to redress the wrongs he had committed.

Repentance is not always a merely personal matter. When transgressions are of a corporate or even national nature, the righteous reckoning can be severe. There are many examples found in the scriptures, but perhaps one of the harshest is recorded by Ezra, the spiritual leader of the Jewish exiles who returned to Jerusalem around 467BC. Ezra confronts the male exiles for breaking the express commands of God by marrying foreign women from the idolatrous and immoral peoples in the land. In spite of this great sin, Ezra acknowledges that God has granted them an opportunity. “Now for a brief moment favor has been shown by the Lord our God, to leave us a remnant and to give us a secure hold within his holy place, that our God may brighten our eyes and grant us a little reviving in our slavery.” Ezra understands that it is God’s unwarranted grace that now makes repentance not only possible but desirable.

According to the record, the great assembly of exiles weep bitterly over their breach of the covenant, but they also recognize the opportunity for genuine repentance. They address Ezra:

“We have broken faith with our God and have married foreign women from the peoples of the land, but even now there is hope for Israel in spite of this. Therefore let us make a covenant with our God to put away all these wives and their children, according to the counsel of my lord and of those who tremble at the commandment of our God, and let it be done according to the Law.”

After three months, the community of exiles finish the extensive and painful task of dissolving all marriages to foreign women.

To our modern sensibilities this seems inexcusably draconian. To sever marriages and families for the sake of corporate integrity seems graceless and cruel. The lead pastor of a large conservative evangelical church in my area recently insisted from the pulpit that Ezra was wrong. The pastor argued that Ezra struggled with fear, legalism, and pride, and that it was out of fear (not zeal for the broken covenant) that Ezra put up boundaries to prevent the Israelites from being influenced by the people around them. The pastor lamented that all this came at the expense of Israel’s influence among the peoples of the lands. It seems that he would not have made the same mistake had he been in charge. No doubt many in his congregation are relieved that their pastor won’t be pulling an Ezra at their church.

Charges of pernicious piety aside, the examples of Ezra, Zacchaeus, and the woman caught in adultery teach us something about the nature of authentic repentance. If repentance marks the end of the transgression, there is no need to address past sin. If it provides personal absolution but does not end the transgression, then repentance requires making amends for past actions. (Of what import is Zacchaeus’ salvation if his victims remain defrauded?) And if the transgression is pervasive or systemic, like that of Ezra’s congregation, real repentance can sometimes demand extraordinary action and hurt like hell. Those who ply a shallow grace offer absolution without alteration. True grace heals the offender and, whenever possible, redresses the offense.

The wounded surgeon plies the steel

That questions the distempered part;

Beneath the bleeding hands we feel

The sharp compassion of the healer’s art

Resolving the enigma of the fever chart.

—T.S. Eliot, Four Quartets

“Those whom I love, I reprove and discipline, so be zealous and repent.”

Revelation 3:19