“And behold, you are to them like one who sings lusty songs with a beautiful voice and plays well on an instrument, for they hear what you say, but they will not do it.”

Ezekiel 33:32

Prophets have a tough job. Their boss is insistent and generally unsympathetic to complaints about working conditions. They’re on call 24-7 and, at the drop of a hat, can be dispatched anywhere for any reason. Their material is a schizophrenic mix of divine reassurances and threats of certain doom, and they are often required to augment their message with acts of dubious nature. They are rarely welcome but instead are greeted with fear, suspicion, or hostility. No wonder. When a prophet shows up, it’s a safe bet that something is rotten in the state of Denmark.

Hecklers and tomato tossers come part and parcel with the job. In fact, the more antagonistic the audience, the more evident is the prophet’s case. That’s the whole point. The prophet appears in order that sin might be recognized as sin, that by his allegations and antics sin might become utterly sinful. The prophet is an instrument of divine correction, and he knows that only when sin is acknowledged can there be hope of salvation. As the author of Hebrews notes, no discipline seems pleasant at the time, but painful. Later on, however, it produces a harvest of righteousness and peace for those who have been trained by it. The crowd may not enjoy the prophetic performance, but some may take it to heart, own up to their iniquity, and find forgiveness.

But the toughest crowd isn’t the hostile one. The hostile mob know that the prophet’s message is meant for them, and so there’s at least a chance that his burlesque will find its mark. The most difficult group to face are the insiders with their box seats and backstage passes. Unlike their hostile cousins, these folk love the show. They know the script by heart and are well acquainted with the elements of prophetic performance. For them it’s a form of religious Kabuki theater, with its elaborate costumes, stylized acting, and dramatic stagecraft. For them the spirit of prophecy is the drama and the dance. The plot is determined by tradition; the prophet is a stock character, and his message is what a prophet is supposed to declaim. For the religious insiders the point is entertainment, not enlightenment. For them, the play’s the thing.

Not long ago, I was hanging with a small group of Christians. We were discussing the scriptures (I don’t remember the topic) and I went off on one of my periodic harangues—an energetic monologue of sorts, or rant as some wryly refer to it. I do remember that it was about the need to shrug off our carefully calibrated Christianity and take seriously the call of the gospel. When I had depleted my supply of brimstone, I awkwardly retreated to my own spiritual territory, and we moved on with our general discussion. As we were disbanding, one of the group paused to privately affirm the gist my outbreak but noted, in so many words, that it wasn’t exactly breaking news. The person pointed out, “You’re preaching to the choir.” We parted amicably, as friends do.

Even so, there was something about the comment that didn’t sit right. There was a trace of presumption in it. A choir member, I thought, would never say such a thing. He would never except himself from a biblical assessment or admonition. He might not like what he hears or understand the personal implications, but he would never consider himself beyond the scripture’s comprehensive reach.

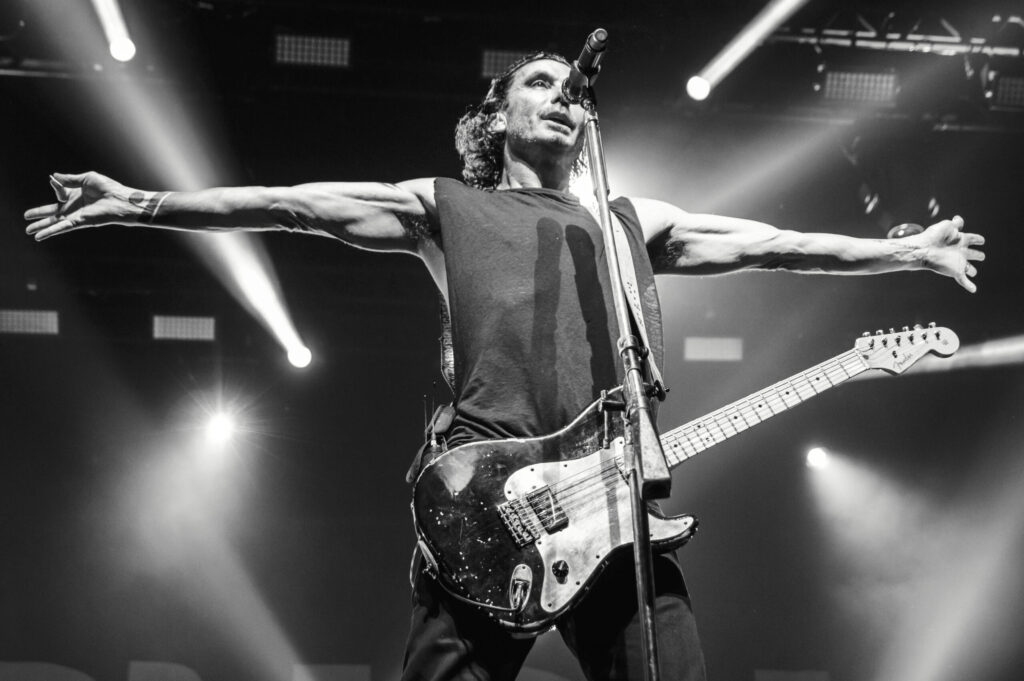

It dawned on me that most American Christians are convinced that they are card-carrying choir members. Those of us who still attend weekly church services sing our songs and then listen (politely or raucously, depending on house rules) to the sermon. But no matter how well-crafted the message, no matter how powerfully we are moved by the speaker’s words, we have no intention of actually heeding what we hear. We are immune to the scripture’s unsettling diagnoses and harsh prescriptions. We are in the club. Sunday after Sunday we gather—whether it be in a traditional church building, a gymnasium, at home, or online—to receive our regular doses of spiritual Serotonin. Some of us prefer a mild hit of intellectual uplift; others crave a soul-shaking, hallucinogenic shot of holy ghost agitation. Still others want a more balanced experience—moderation in all things. It doesn’t matter. We have come for the show. We desire to be charged, not changed.

And so we have gathered around us a great number of teachers to say what our itching ears want to hear. Give us the reasonable or the rabble-rouser. Give us the hip and culturally savvy. Give us the chatty or the spiritually sublime. Give us a sweatshirt or a suit and tie. Give us a pulpit-pounder or tattooed troubadour. Give us a shaman! Give us a showman!

Whatever.

Later on, after the performance, the prophet retreats to a sparsely furnished room. He sits on the edge of the bed. All is quiet except for the muted ticking of the clock on the wall. Tomorrow’s another day. With a sigh, he folds his damp shirt and wrinkled pantaloons and lays them on top of the others in an old, battered suitcase. The crowd was enthusiastic this evening, he thinks. They seemed to anticipate and applaud his every pronouncement. It could have gone worse.

But the prophet’s been around. He knows. He sees the worm at the root of the rose. He remembers his job. “This is the one to whom I will look: he who is humble and contrite in spirit and trembles at my word.” He adjusts his camel’s hair coat, tucks the well-thumbed script under his arm, and heads toward the station. A voice whispers in his ear: “When this comes—and come it will—then they will know that a prophet has been among them.”

Yes. But until then . . .