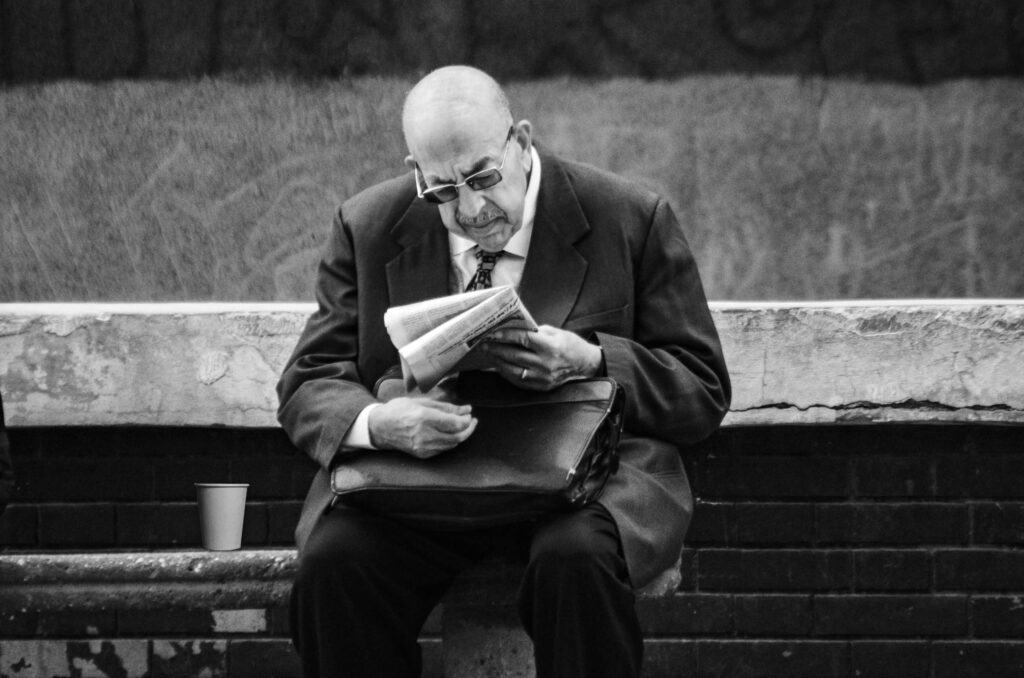

Like everyone else who makes the mistake of getting older,

I begin each day with coffee and obituaries.

Bill Cosby

One day, some twenty or more years ago, my 85-year old dad and I were working on something in his yard in the little town of Deering, North Dakota. It was a bright, windy day, so typical of summer on the northern prairies. Out of the blue he paused and looked at me. “I don’t know how I ended up an old man,” he said. “On the inside I feel the same, but on the outside I’ve gotten old.” That was it; he did not elaborate. We returned to our task and he never mentioned it again.

He’s gone now and sleeps in a small, hardscrabble cemetery outside the little hometown he loved. But that moment remains as clear and crisp as a North Dakota day. My dad was surprised by what others before him had likewise discovered. As Emily Dickinson noted, Old age comes on suddenly and not gradually as is thought. Aging can often seem more of an ambush than a devolution.

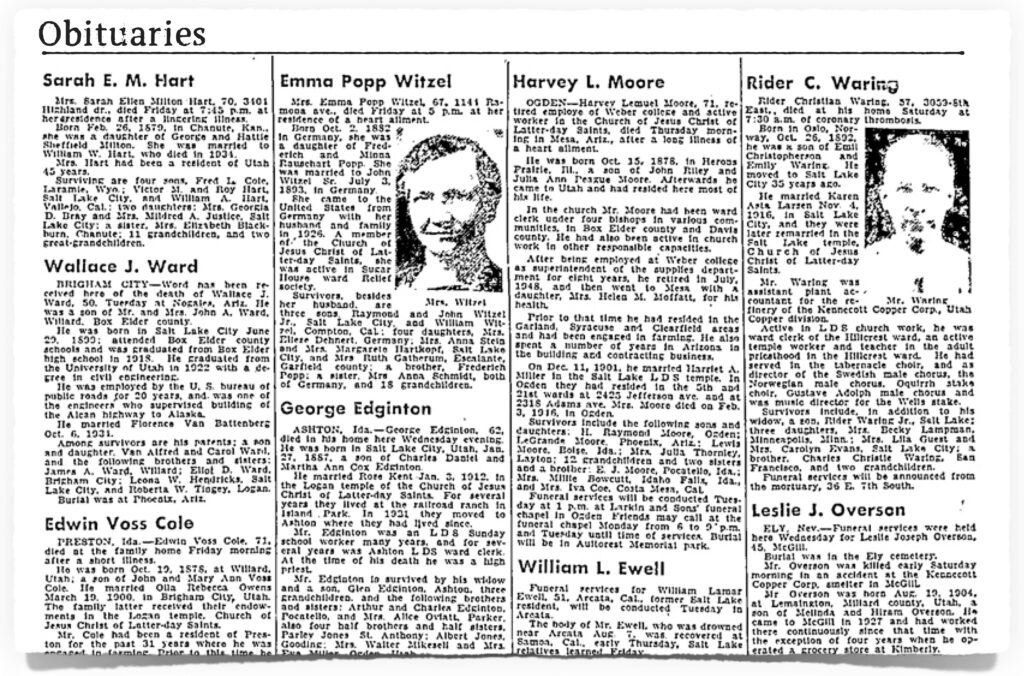

I confess that for some time now I have regularly checked the obituaries of my hometown newspaper. I’ve noticed that the birth years of the deceased are steadily creeping toward my own. The death of former classmates, whether I knew them well or not, always inflicts a quiet stab of loss. There is something poignant to me about the passing even of those I do not know. Formal portraits, photographed decades ago, show young faces glowing fresh and vibrant. Casual snapshots, barely usable for publication, hint at the last-minute scramble of loved ones caught unprepared by so abrupt a departure. And, of course, there are the expected faces, photos taken at a 90th birthday party or drawn from a church directory. Every entry is the record of a life lived, a brief argument against the long forgetfulness of the grave.

Awareness of mortality does not necessarily mean morbidity. Confronting the stark reality of death can serve to magnify the exquisite value and joy of life. This is especially true for those whose ultimate hope lies beyond the circles of the world. Years ago, before I had attained to that vague milestone known as middle age—an achievement which I have, arguably, already left behind—I was moved to pray this verse from the Psalms: Teach us to number our days, that we may gain a heart of wisdom. The insight seemed simple enough; acknowledging that I had a limited engagement was a pillar of wisdom. What I did not anticipate was the answer to that prayer. Ever since, I have heard the ticking of the clock. I admit that at times it has disturbed me like the watch in Poe’s story The Tell-tale Heart. It can seep into even the most delightful moments. But strangely, and more often than not, this sober intrusion also infuses a transcendent glow, lifting the moment out of the moment to reveal an elusive beauty that makes the heart ache with longing.

In Frank Capra’s beloved movie It’s a Wonderful Life a man on a porch berates young George Bailey who is reluctant to surrender his affections to 18-year old Mary Hatch:

Man: Why don’t you kiss her instead of talking her to death?

George: You want me to kiss her, huh?

Man: Ah, youth is wasted on the wrong people!

Here is enacted the age-old conundrum. The young have life but little wisdom; the old have wisdom but little life. Perhaps that’s what the psalmist seeks to address. The sooner I recognize that life is fleeting, the sooner I can embrace a truly wonderful life.

The ticking of the clock is also a reminder that time does not stand still. Each passing moment is a moment forever gone. God may have access to the past, but we do not. Wisdom learns from the past but is not trapped by it. The Apostle Paul strives to make the most of every opportunity—forgetting what is behind and straining toward what is ahead. He knows that meaning is not sourced from the past but from what is yet to come. He exhorts the Corinthians: Do you not know that in a race all the runners run, but only one gets the prize? Run in such a way as to get the prize. A meaningful life is not a matter of duration but of purpose. Even so, it’s the tick tick tick that gives the journey its urgency.

King David was once the ruddy, youthful darling among Jesse’s sons. But he too knew what it meant to age. I was young and now I am old, he wrote and referred to his once robust body as this leaning wall, this tottering fence. Such is the fate of all who are born into the world. As Isaiah cries: All flesh is grass, and all its beauty is like the flower of the field. Learning to number our days does not alter that. What it does do is charge our days with significance. Life is not a generality; it is manifest moment by moment—and only in the moment. There is no future, only the coming now.

Echoing King David, the poet William Butler Yeats wrote that an aged man is but a paltry thing, a tattered coat upon a stick. Those who know the aches and pains of growing old might concur. There is no escaping the stubborn realities of aging. But the end of our days need not be gloomy. The proverb declares that the gray hair of the righteous is a crown of splendor. And even though it is appointed for man to die once, there is great peace for those who have learned true wisdom. As William Wordsworth writes, An old age serene and bright, and lovely as a Lapland night, shall lead thee to thy grave. Serene and bright and lovely? Yes, please.

Live so that when the final summons comes you will leave something more behind you than an epitaph on a tombstone or an obituary in a newspaper.

Billy Sunday