“Thou hast created all things, and for thy pleasure they were created.”

Revelation 4:11

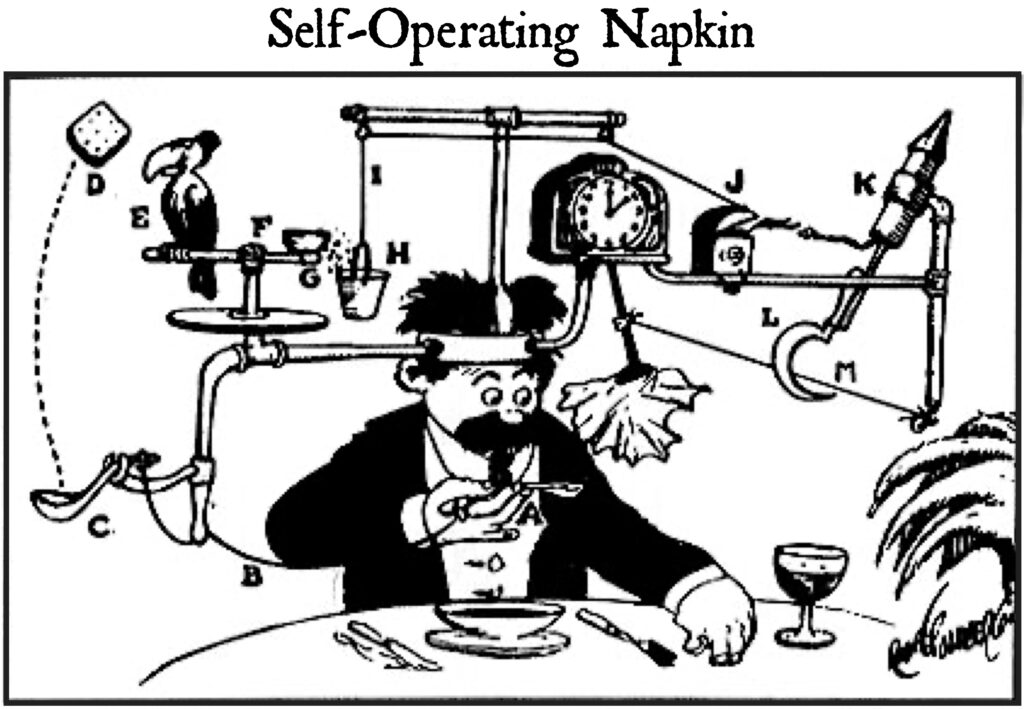

Most people of a certain age remember Rube Goldberg’s drawings of delightfully convoluted mechanisms. Goldberg designed ridiculous contraptions to accomplish the simplest of tasks. His machines consist of a series of simple devices, each triggering the next, which eventually achieve a goal. Our delight is not in their efficiency but in their silliness. Goldberg’s machines are outlandish and unnecessary, but that’s the whole point. That’s why we like them.

The scientific mind has little sense of humor. Its mandate is to explain, and so it flounders without reasonable explanations. The scientist assumes that everything is necessary (cause/effect) and that the great task is to figure out why. It would be scientific blasphemy to admit flapdoodle into the system. For science there is no such thing as true impracticality or absurdity; there are only undiscovered justifications. Ironically, this rather pinched perspective has led scientists to create a number of their own Goldberg variations.

The evidence, however, overwhelmingly suggests that God is a Rube—or at least moonlights as one on his day off. Within the universe’s meticulous latticework of interdependence, there are countless cases of sheer creative excess. Of course, it would be impossible to point them all out, but divine frivolity could be organized into a few general categories.

Beauty is the greatest enigma. Science has tried to make it a utilitarian feature, but in most cases beauty is not a functional necessity. The physics of a sunset do not depend on whether or not we find the phenomenon pleasing. A world without Van Gogh or Beethoven would no doubt be a poorer place, but we would be hard pressed to explain in scientific terms exactly why. The profusion of flowers in a meadow may attract bees, but that’s not what makes them lovely. We may be able to describe certain features that make something beautiful to us (variation, symmetry, etc.) but explaining why those features appeal to us in the first place is another matter. Beauty is about beholding, not comprehending. The poet W. H. Auden acknowledges the frivolous nature of the beaux-arts when he confesses, Poetry makes nothing happen. Or to quote the slightly less polished Rolling Stones, I know it’s only rock and roll, but I like it. Utility is a transaction. Beauty is a bonus.

Another category is the just plain ostentatious. If beauty aims for proportion, ostentation goes for overkill. It’s the crazy aunt who wears too much lipstick and jewelry. There are so many examples of frivolity in the natural order it’s almost commonplace. There’s the peacock with his pimping tail and his spiky aquatic counterpart, the lionfish. There are the mesmerizing murmurations of starlings or the lyrebird of southeastern Australia that can mimic the sounds of all the other birds he hears around him—and the sounds of chainsaws and camera shutters too. And the mandrill with its prismatic proboscis. And the flamboyant cuttlefish whose morphing patterns would be at home in Times Square. Here’s to the showoffs of the world whose mantra is Look at me! Look at me! Look at me! When it comes to fashion, attitude is everything.

Sometimes the frivolous takes the form of the quirky. In these instances it seems that the creator is either doing some beta testing or he’s simply trying to use up extra parts. The electric eel is a good example. It’s like God put an 800-volt battery in a sock then threw it in the water to see what would happen. And no list of the peculiar would be complete without mentioning the platypus. There is absolutely no excuse for the platypus. Even God can’t explain this one, which means he’s not even going to try.

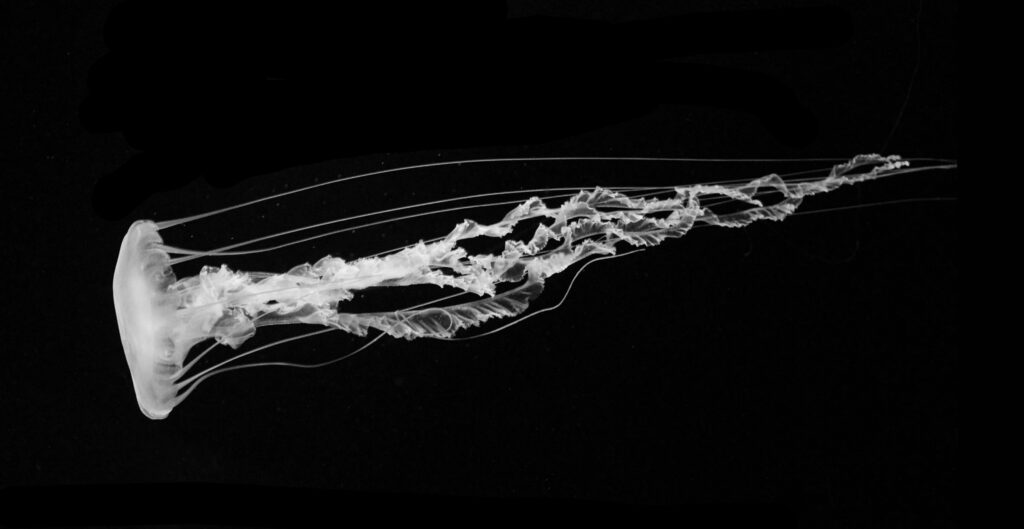

A subcategory of the quirky is the starkly alien. Whereas the quirky are odd combinations of otherwise familiar elements, the alien are so foreign to our sensibilities as to seem otherworldly. The tiny tardigrade is nearly invincible, able to survive extreme temperatures, extreme pressures, air deprivation, radiation, dehydration, and starvation—that would kill other forms of life. The earth’s oceans are home to some of the most alien creatures of all. The very intelligent octopus who has a central brain and smaller brains in each of its eight legs. The most otherworldly creature of all may be the jellyfish. What to make of such an exotic being? As Hamlet said, “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” Yes, indeed.

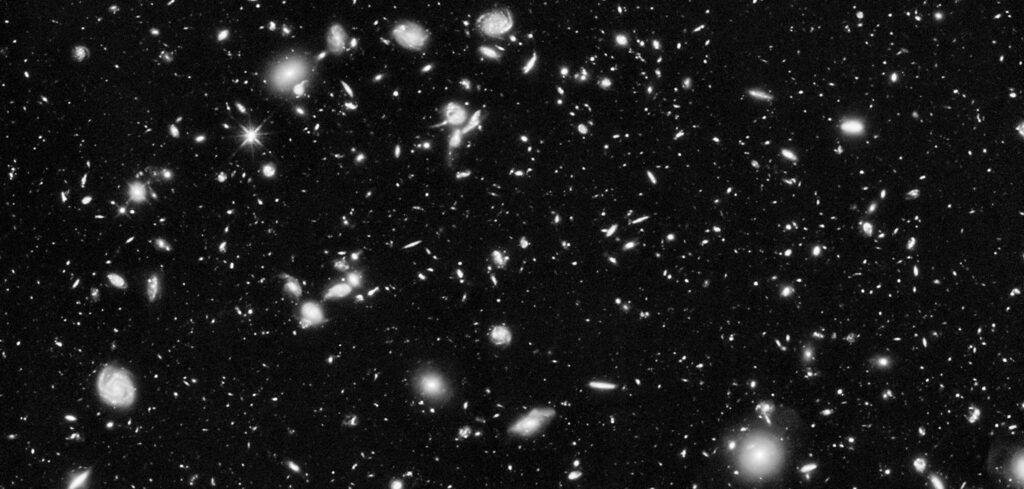

Perhaps the most astonishing frivolity of all, however, is the incomprehensible vastness of space. No one knows the extent of the physical universe, and what we do know defies meaningful context. The Milky Way, our home galaxy, is about 100,000 lightyears across and contains at least 100 billion stars. The size of the entire universe is unknown, but the observable universe contains an estimated 2 trillion galaxies. Some calculations suggest that there could be around 10,000 stars for every single grain of sand on earth. This has led some to insist that there must be other intelligent life elsewhere in the universe, that it would be the height of human arrogance to think that we are unique in such a vast place. But why not? The average house in America is 2,300 square feet. Does a family need that much space to survive? The entire population of the world—8.2 billion—could fit (with room enough for each person to spin around with their arms extended) in an area the size of the big island of Hawaii. Does this mean that the earth is too big for us?

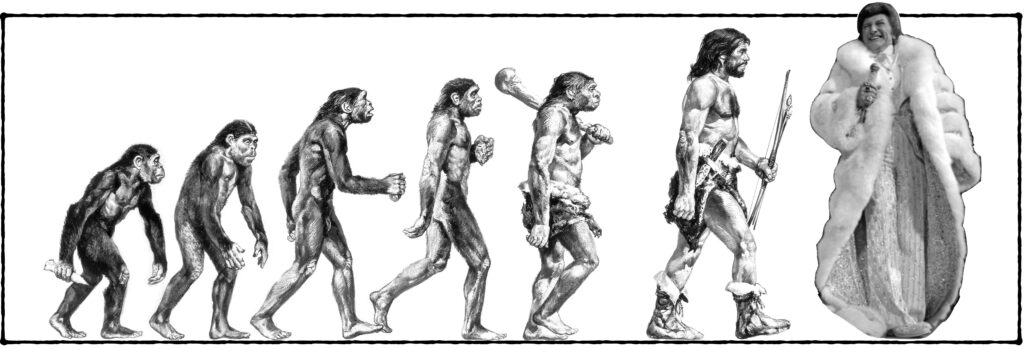

What it does mean, as do all these other examples, is that we are surrounded by the frivolous acts of God. In fact, since necessity did not compel God to make anything at all, that he did so for the sheer delight of creating itself, it would not be too much of a stretch to say that everything that exists, from the amoeba to the angel, reflects the gaiety of God. Humankind matters, not because God had to make us, but precisely because he didn’t.

I, for one, am glad he did.