And Jesus said to him, “Do you see these great buildings? There will not be left here one stone upon another that will not be thrown down.”

Mark 13:2

Enthroned atop a knoll overlooking the 205 just south of Portland rises a massive church complex. Commuters are hailed by a modern, multi-storied construction that could be mistaken for the campus of a giant Oregon tech company if it weren’t for three crosses boldly crowning the facility. The impressive façade, strategically angled toward the freeway, is intended to capture the 65mph attention and signify an attractive, thriving, and well-funded Christian enterprise. The statement is clear: this is a big, successful congregation—a brand unto itself.

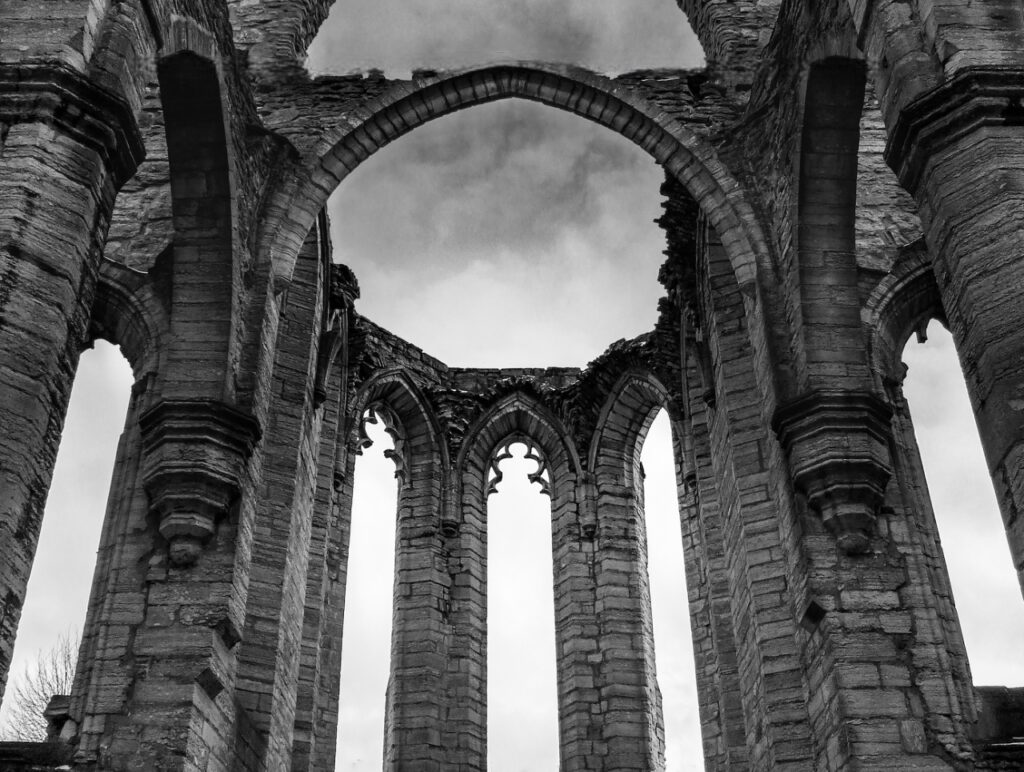

The precedent for grand religious architecture goes way back, of course. There are the shrines of ancient Egypt, the pagodas of Asia, the stately sanctuaries of Greece, and, perhaps greatest of all, Solomon’s magnificent temple in Jerusalem. The Christian contribution culminated in the many cathedrals erected across Europe during the Middle Ages. These imposing cathedrals were expressly designed to exhibit the grandeur and glory of God. As Pope Benedict XVI observed, “All the great works of art, the cathedrals—the Gothic cathedrals and the splendid Baroque churches—are a luminous sign of God, and thus are truly a manifestation, an epiphany of God.” Edifice as epiphany. Lofty appraisal indeed.

By comparison, church buildings in the New World are far humbler. With the exception of a few notable examples in the big east coast cities, American’s tended to embrace smaller, simpler houses of worship. The Puritan spiritual identity found its expression in the plain white meeting hall which evolved westward into the iconic little steepled churches that still dot the rural American landscape. Although modest, these unassuming structures assumed the same divine manifestation as their ostentatious kin. Whether in a backwater village or on the vast, open prairies, a little white church visually signified the very presence of God.

The advent of the American megachurch renewed the pursuit of gargantuan religious splendor. New titanic sanctuaries, dwarfing even the greatest Old World cathedrals, vie for dominance. Their jaw-dropping size overwhelms the eye, and for awestruck acolytes these proud glass and steel behemoths are proof-positive that the God of Grandeur is present and accounted for.

For most of us, however, the most recognizable symbols of American Christianity are the neighborhood church buildings found in virtually every city and town. Functionally adorned, they have long signified, to believer and unbeliever alike, that God and his sanctioned tabernacles dwell in our midst. Though less commanding than Europe’s imperial cathedrals, Pope Benedict’s observation holds true for these commonplace tabernacles too: the edifice is an epiphany.

But something has changed. Whenever I pass by a church building these days, a strange awareness emerges. Instead of perceiving a familiar testimony of divine reality, I am struck by a profound sense of vacancy. The structures that for so long had served as a “luminous sign of God” now seem to manifest only absence. The building is a house of bones; the edifice is empty.

I sense, too, that this is not simply a reminder that church is the people, not the buildings in which they meet. No, this is something else. It is about the face of Christianity. This is an intimation of judgment, of a divine visitation marked by abandonment. And it’s been a long time coming.

The scriptures illustrate God’s willingness to abandon the edifices associated with his presence, even those he himself ordained. In one instance, when the army of Israel is being defeated by the Philistines, Israel sends for the Ark of the Covenant, which they believe will save them. But Israel not only loses the battle; they surrender the Ark as well. The Holy Box, it turns out, is just a box. The prophets also learn this hard lesson. Years later, as Ezekiel sits among the exiles in Babylon, he envisions the glory of the Lord withdraw from the great temple. Jeremiah beholds the destruction of Jerusalem and laments, The Lord has rejected his altar and abandoned his sanctuary. The city of God and the temple bearing his name lie in ruins. The edifice is erased.

And it is happening again. Our church buildings communicate nothing to the current culture, except, perhaps, a tired, irrelevant piety. Our liturgies—the conservative to the charismatic—have become, as Isaiah prophesies, precept upon precept, precept upon precept, line upon line, line upon line, here a little, there a little. The structures that once housed and manifested the reality of Christ are being abandoned by the Spirit and exposed as the shadows they have always been.

This should come as no surprise. Divine judgment is increasingly apparent to those whose eyes are open. But it not only is coming upon the kingdom of the world. As Peter declares, It is time for judgment to begin with the household of God. And begin it has.

“Once more I will shake not only the earth but also the heavens.” The words “once more” indicate the removing of what can be shaken—that is, created things—so that what cannot be shaken may remain.

Hebrews 12:26-27