“If I look confused, it is because I am thinking.”

Samuel Goldwyn

The unexamined life is not worth living, said Socrates. One of the most important distinctions between humans and other animals is our ability to reflect upon our own existence. The famous dictum is literally translated the unexamined life is not lived by man. Socrates believed that to live without contemplation is not to live as a human at all. Absent deliberate thoughtfulness, we are but base creatures of instinct or, according to the psalmist, brutish and ignorant like a beast. Our capacity for higher thought is what sets us apart in the material world. As Blaise Pascal has noted, Man is but a reed, the most feeble thing in nature, but he is a thinking reed. We may be dust in the wind, but we are dust with minds. To invert René Descartes: I am, therefore I think.

For many, thinking is mostly a means to an end. Reason is the ability to solve problems, and once a problem is solved there is nothing left to think about except the next problem in line. Human life is comprised of a series of challenges to be addressed and overcome. There may be a few collateral perks along the way, like the Mona Lisa or Mozart or macaroons, but human existence is essentially a string of “if X then Y” propositions. The answer to “Why?” is always “X.” This suffices.

Unfortunately, such reduction can lead to a rather disenchanted journey, even for a theist. For the Christian, it can take the form of a very un-Socratic axiom: “The Bible says it; I believe it; that settles it.” Inquiry is seen as a form of doubt, or at least an impious waste of time. This perspective, however, can be seen as a kind of intellectual laziness—or even cowardice—and has led many, including the famous 20th century philosopher and futurist, Buckminster Fuller, to conclude: Belief is when someone else does the thinking. Intellects far greater than Fuller’s would take exception to that, but it is true that many saints seem indifferent to anything beyond practical, how-to Christianity.

Over the years I have heard believers proclaim many things about God. They have testified that God is good, that God is holy, that God is powerful, that God is gracious, that God is wise. I have heard them proclaim that he is righteous, merciful, and just. But in all those years, I have never heard someone boldly declare that God is interesting. Among the believing rank and file there seems to be a strange lack of actual curiosity about God. I have found zeal for service; I have found passion for worship; I have found affection for the church; I have found reverence for the scriptures. What I have rarely found in the average layman, however, is a genuine inquisitiveness that compels someone to explore, for exploration’s sake, the astonishing nature and work of God.

When Jesus was asked which was the most important commandment, he answered, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind and with all your strength.” We’re familiar with the heart aspect of love; the heart is the seat of the emotions. Loving God involves an emotive response. A purely intellectual ascent to his greatness is not love; it is theory. Soul simply means life, the individual’s being. As the poetic King James renders man’s creation: The Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living soul. Soul is an umbrella term under which all the aspects of life are housed. To love God with all our souls is to surrender without reserve our whole selves to him. And to love God with all our strength means, as Paul has it, to honor God with your bodies. Heart, soul, and strength are concepts easily grasped.

To love God with all our minds is not so easy to parse. The best most can offer is that it means to think about God a lot. It’s hard to argue with that, but it’s not very enlightening. Jesus’ answer implies that we are to love God with all the conscious capacities of the mind. Those capacities are reasoning, memory, and imagination. We have already alluded to the mind’s ability to reason things out. To love God with our minds does indeed involve a deliberate seeking, sorting, and solving. This is how the devout scientists of old understood their mandate. This is also the motivation for theology, what thinkers of the High Middle Ages used to refer to as the Queen of the Sciences. Scientists searched out the how; theologians explored the why. Both thought of their vocations as a form of divine adoration. For Christians especially, grappling with unanswered questions, whether terrestrial or heavenly, is an expression of love for the God who made all things.

To love God with our minds also employs memory. The mind’s capacity to retain information is fundamental. As the heartbreaking reality of dementia underscores, memory is essential for personhood; we are the sum of our experiences. An individual is who he remembers himself to be. That is one reason why the scriptures so often exhort the Hebrews to store up in their minds the decrees of God. Fix these words of mine in your hearts and minds; Moses commanded. Tie them as symbols on your hands and bind them on your foreheads. Jesus informs his disciples that the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, will teach you all things and will remind you of everything I have said to you. To commit to memory who God is and what he has said, and to recount his blessings and faithfulness, is not only to express love for him but to remember whom he has made us to be.

With regard to love for God, the least appreciated capacity of the mind is imagination. The word itself reveals its meaning. To imagine is to create a mental image. Such an image is not limited to real world experiences. The mind is able to create powerful experiences of its own. Some can be terrifying like forebodings or nightmares; others can be uplifting or frothily delightful (think: unicorns). The capacity to imagine things beyond the natural order seems less frivolous when we recognize its crucial role in our relationship with God. The mind’s ability to travel beyond the provincial earthly realm enables us to spy what worldly eyes cannot. Through the imagination vision becomes visionary. The mind can see what the eye cannot, and this can prompt wonderment and worship. To love God with all our minds means entertaining glories only apparent (at least for now) to the mind’s eye.

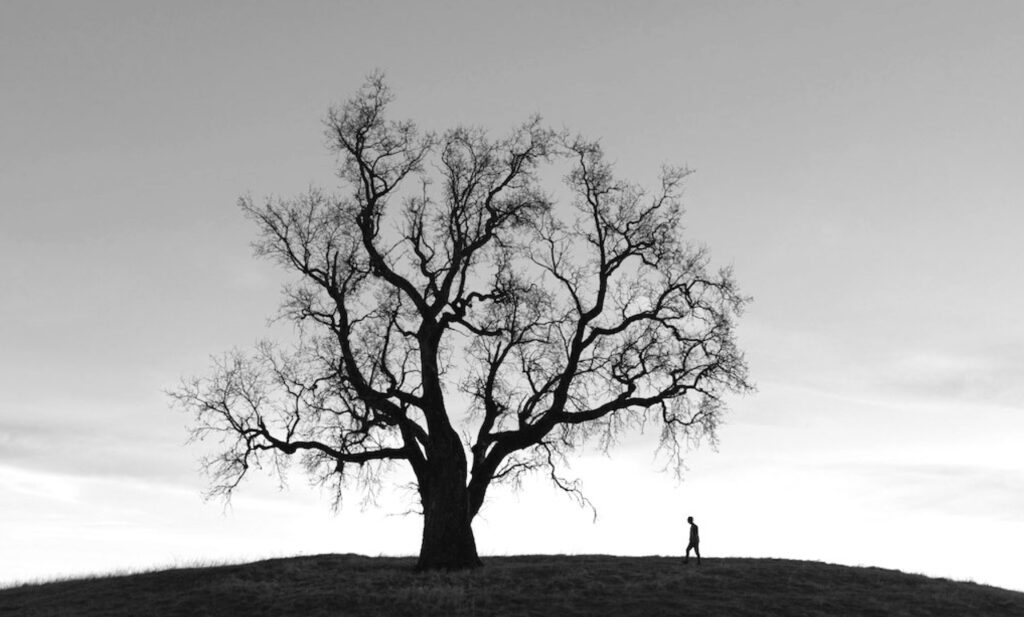

I am not advocating for so-called mystical contemplations of the divine. I am speaking of the joys of thinking itself. Even the psalmist wasn’t locked into a rigid religious rubric; he often let his mind wander among the universe’s countless marvels: I will ponder all your work and meditate on your mighty deeds. Sometimes it is good to set aside all the practical and religious demands of daily life and just ponder, not to solve problems or satisfy vague obligations, but simply to explore—to think for thinking’s sake. It may not produce a winning argument or great invention, but as playwright Arthur Miller cautioned, “Don’t be seduced into thinking that that which does not make a profit is without value.”

Think about that.

“There are no dangerous thoughts; thinking itself is dangerous.”

Hannah Arendt